A Geologic Road Trip to Bears Ears National Monument

- Bluff Dwellings Resort

- January 29, 2023

- Things To Do

Words and photos: Jan Noirot.

I answered without hesitation. “The 128 south of the I-70 to the 191 all the way south to the 163 to Monument Valley.” Surprised, they asked why. Why was it my favorite road in the country? There is little doubt in my mind why, but how to find the words?

“Rocks, I think,” I answered. Rocks?! The word itself conjures skinned knees and pebbles in patches of skin where I fell off my bike, and sneaky ones that grabbed my tennis shoes and introduced my face to the ground. Let me now introduce you to the geology of my favorite road in the entire country, on a road trip to Bears Ears.

It all began 500 or 600 million years ago when the area alternated between being the bottom of a sea and being the alluvial fan (that is, a deposit or accumulation of sediments fanning outward from a source) of gigantic inland erosion. This alternation gave the area its color—red, white, green, purple, and yellow. Then tectonic activity elevated the Colorado Plateau like a gigantic bubble in North America roughly 250 million years ago.

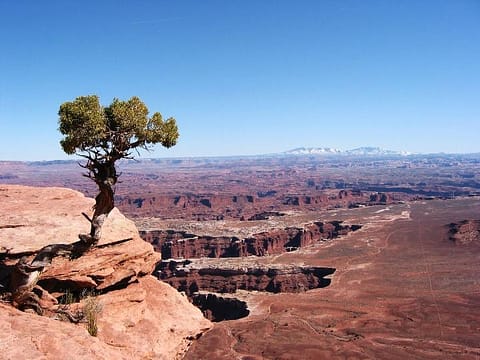

The laccoliths that now form the La Sal, Henry, and Abajo mountains rose above the plateau further yet, providing backdrop and scale to the vast lands. Those mountains now rise to an elevation of 13,000 feet, the plateau hovers around 6,000 feet, and the Colorado, Green, and San Juan rivers cut down through the plateau to as low as 3,000 feet. That leaves 10,000 vertical feet for the wind, water, and us humans to play with. Nearly two miles of vertical! The resulting mesas, canyons, pinnacles, arches, synclines, and badlands are so unique and impressive that there are three national parks (including two separate districts of the Canyonlands), four national monuments, a national recreation area, several state parks, and a Navajo Tribal Park along or near my favorite road.

While Utah Route 128 begins rather inauspiciously from Interstate 70, winding across monochrome mud heaves, it soon joins the Colorado River and quickly reveals hints of the treasures ahead. A dark rock on the right has well-preserved petroglyphs telling us we are not the only ones who loved the area. The hanging cables of an old suspension bridge swing in the breeze, and a moment of nostalgia hits as I remember waiting our turn to line up the jeep tires on the planks that crossed the ties to cross the river.

Quickly, the burgundy cliffs rise above the river with chiseled faces and cracks. Deep maroon reflects in the river and reflects off the bottoms of the clouds above. This Wingate formation of sandstone bookends the entire region. As the river descends, the cliffs rise from 400 feet to 1,600 feet in Castle Valley. The road must wind and bend back on itself and there is no other choice but to follow the river. The massive erosion has left behind soaring towers and knife edges that call to the eagles and vultures—and rock climbers.

At Moab, one can go right on U.S. 191 to Arches National Park then continue further to Route 313 to access Dead Horse Point State Park and Canyonlands National Park. Canyonlands and Dead Horse Point put you on top of the Wingate formation that you just drove through, but at twice the height. The view at Grandview Point and Green River Overlook is a staggering 1,500 feet to the White Rim level, and then from White Rim to the river is another 600 to 1,000 feet. It is beyond the mind to comprehend the distance. How does one understand a half-mile drop to the river? I wish I could be an eagle for a moment and soar.

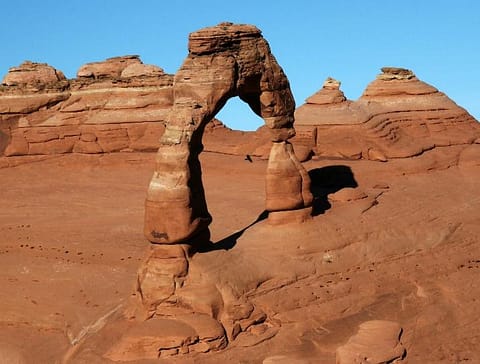

Arches is a completely different story. The Entrada formation sandstone is not chiseled and thick like the Wingate. It is warm colored and rounded, made of petrified dunes. Wind and water have eroded the stone into fantastic fins and holes and the world’s largest concentration of arches. Many of them are freestanding while the surrounding material has washed or blown away. What I also love is that all the wind-blown grains of sandstone usually wind up deposited behind another rock as a dune. It feels so good on bare feet after a long day’s hike to run and jump and slide in it—and there is a big dune right across from the park entrance!

Entrada sandstone surrounds Moab and continues south into the Behind the Rocks area and out onto the plain of Dry Valley. Right beside the road are two large freestanding arches. Wilson Arch is visible right from U.S. 191. Looking Glass Arch is about two miles down a labeled dirt road, but nearby.

As a child, Church Rock would really get my excitement going―and it still does today!. The basilica-like rock is on the east, and the road to the Needles District of Canyonlands heads west. The Needles area is intimate, up close, and personal. Creeks and washes cut through Cedar Mesa sandstone in winding, twisting, arch-building, spire-building ways. I have fond memories of running, scrambling, sliding, and getting lost in the maze of stone. There is one rock with a sideways hole in it (called a “potty”). I have two photos of it. One is recent with me standing in the hole looking like a sous-chef with rock all around, the other is the same shot, but I am eleven, with a friend, and only our heads stick up.

Once 191 continues south past the Abajo Mountains, the rock possibilities open like an apron. To the east lie Hovenweep National Monument and Canyons of the Ancients, where the ancient peoples known as Ancestral Puebloans (or sometimes still called “Anasazi”) shaped and stacked and painted rocks to make their homes. Their architecture rivals that of any age.

To the southeast is a valley of hoodoos and goblins that spur the imagination. Not far away is the San Juan River which has been a lifeline to humans and critters for more than 14,000 years. Clovis points (sharp, fluted projectiles) and mammoth petroglyphs have been found there. U.S. 191 briefly turns westbound at the town of Bluff (you’ll know you’ve arrived there when you emerge from Cow Canyon and Bluff Dwellings Resort and Spa pops up on the east and the iconic Twin Rocks formation comes into view on the right), before turning due south again. Our journey continues on U.S. 163. As the river snakes its way to Lake Powell and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, it spends 6 miles traveling just 1.5 horizontal miles at Goosenecks State Park, where one can view four lengths of the river from one spot.

To the southwest is another uplift called Cedar Mesa that comprises most of Bears Ears National Monument. One could spend a lifetime exploring the remote and rugged canyons formed out of the colorful red and white Cedar Mesa sandstone. The best access to the canyons and mesa top are from the north or from the south on one the most dramatic roads in the country. The 261 road drops 1,000 feet as a single lane called the Moki Dugway, zigzagging down the cliffs. Though unpaved, the gravel road is generally in good condition (except when wet) but vehicles hauling trailers are prohibited. For the rest of you, the views are fantastic!

On the way to Cedar Mesa the road cuts through the hundred-mile-long Comb Ridge monocline. A single fault event thrust a ribbon of Cedar Mesa sandstone 400-800 feet to the skies, forming teeth and valleys filled with pools and slots and, after early humans lived in then abandoned the area, ancient ruins. The San Juan River cuts through it once. Two modern paved highways cut through it. The ancient ones cut half a dozen hand and toe trails up and over this formidable ridge.

To the northwest lies Natural Bridges National Monument. Three of the world’s largest stone spans are in close proximity. Each has their own personality and can be viewed from easy overlooks above or more strenuous hikes underneath. This little known park is so spectacular that it will be featured in its own blog.

The end of the Bears Ears road trip for this story is at Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park. These iconic dark red buttes and mesas are so recognized the world over because of movies such as True Grit and Forrest Gump. There is even a wide and slow (25 mph) spot in the road called “Forrest Gump Hill,” where travelers can stop and take the same photo where Forrest stopped running.

The mood presented by these creatively shaped rocks varies every visit. Sun, clouds, fog, sandstorms, snowstorms, and time of day, make it seem a completely different place.

So it is rocks that have impressed me for a lifetime and given me adventures in them, around them, on them, and driving past them that makes the drive from I-70, down the 128, and down the 191 and 163 my favorite roads.